I just picked up a bound volume of League of Nations documents that our library kindly procured for me via ILL and as the student worker was checking the book out, he and I noticed that the entire history of the book was there on the inside back cover (see images below). This is something we will (mostly) lose through the various scanning projects underway,which don’t always capture images like those below.

The book itself was published in the late 1930s. The first bit of useful data tells us that it was bound in North Manchester, Indiana in August 1967. The Heckman Bindery was acquired some years ago by the HF Group, so it still has a sort of existence. Interestingly, HF Group will be happy to convert your analog products to digital files.

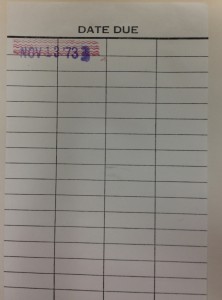

The next bit of physical data we get on the history of this book is evidence that it was not so popular during the days when librarians stamped due dates in the backs of books. As you can see, this one was checked out exactly once during the days of the due date stamp. I don’t know when the AU Library (owner of the book) went to an IBM punch card system, to switch to that system they did, as the next image demonstrates, but I’m sure if I bothered to call the library, someone could tell me.

This artifact of computers long gone tells us nothing historical, other than that librarians worried about those punch cards being mistreated. The patron is informed that “A charge will be made if this card is mutilated or lost.”

Finally, we get the current cataloging system’s artifact, the ubiquitous bar code. Without access to the screen that appears for the librarian when the bar code is scanned, the patron can learn nothing at all from this bar code.

In addition to being a walk down memory lane for me, these various artifacts of library information systems of yore (and the present) made me wonder about the shifting access to information about the book. We never could know who checked out a book and for how long, but the old back of the book due date stamp system at least gave us some indication of how popular the book was, even if it only told us that one person checked it out over and over and over. At least we could know that it was being checked out. Now all circulation information is available only to the librarian who can see the screen when the bar code is scanned.

Which also makes me wonder how difficult it would be for libraries to make circulation data (not who, but how often and for how long) about books available. It’s quite possible that such data are already available. I just haven’t asked for it. We talk a lot about how often an ebook was downloaded, but in those conversations we almost never discuss how often a book was checked out. Such data might just enrich our conversations about the public reception of a work of scholarship.

Â